Blinky Palermo was born Peter Schwarze in Leipzig, Germany, in 1943. He entered the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1962, where he studied with Joseph Beuys. As of 1964 he appropriated the name of American boxing promoter and organized crime figure Frank “Blinky” Palermo. After visiting New York with Gerhard Richter in 1970, he established a studio there in 1973. Palermo died at the age of thirty-three in 1977 while traveling in the Maldives.

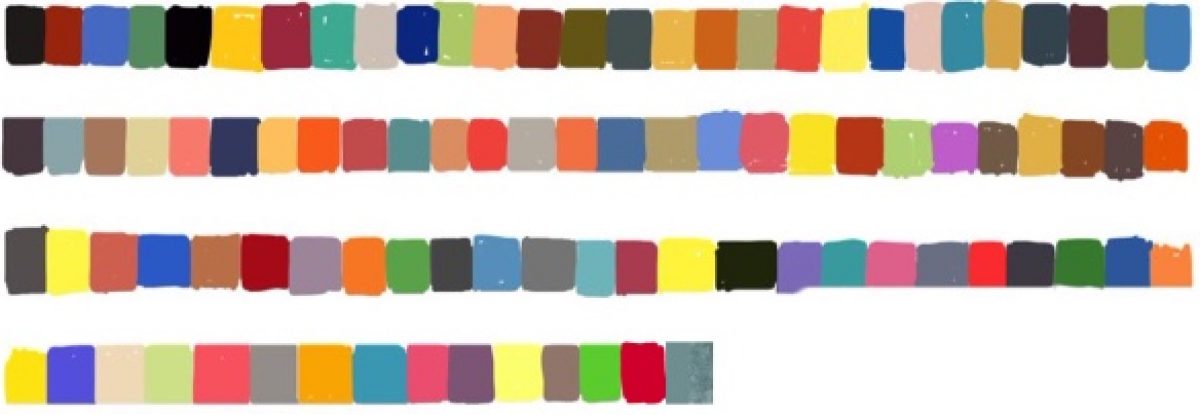

Palermo left us with four distinct bodies of work, and as different as they may look on the surface, they have in common an abstraction that is always saturated with the marks of its time. Take the “Stoffbilder,” the so-called cloth pictures. From 1966 through the early ’70s, Palermo would shop local department stores for lengths of commercially dyed monochrome cloth. He would have two or three of these sewn together (initially by his first wife, Ingrid, and later by Richter’s first wife, Ema) and then mount the joined bands on stretchers usually measuring two by two meters (roughly six feet six inches square). The cloth pictures convey Palermo’s passion for color and its combinations: bright blue and red; orange and dark blue; pink, orange, and black; light blue, green, and red. The palette became more vivid over the years, especially as combinations of three colors pushed aside the simpler pairs, but Palermo carefully orchestrated the works’ installation to let more subdued combinations radiate as well. In a one-man show at the Konrad Fischer gallery in Düsseldorf in 1968, for example, he alternated pictures made of intense and bright hues with more restrained ones—a feast of color. The fabrics were common stock at a time when bold colors dominated interior decoration, clothing, and advertising, reflecting the progressive and optimistic spirit that had captured the German imagination despite the waning of the postwar economic miracle. In fact Palermo may have abandoned the silks he initially used for these works in part because they looked too precious—not common enough, not straight out of his neighbor’s living room.

Even more than the cloth pictures, the wall paintings venture into decoration, embraced in the late nineteenth century by artists like Paul Gauguin as a way to overcome the burden of mimesis, but later feared and shunned by pioneers of abstraction like Wassily Kandinsky. Today, thirty years after Palermo’s example, decoration is once again fertile ground for artists as diverse as Liam Gillick, Chris Ofili, Laura Owens, and Fred Tomaselli. For his nearly thirty wall paintings, Palermo drew lines on architectural surfaces or covered them with monochrome fields of color, often highlighting spatial characteristics of a room or adding ornamental features. Made over a five-year period beginning in late 1968, the wall paintings largely overlap with the sewn paintings. While the two bodies of work couldn’t look more different, they share an interest in long-forbidden territories and muddied categories.

Palermo’s move to New York, shortly before Christmas 1973, could hardly have surprised anyone. His previous visits—once with Richter, once with his second wife, Kristin—had whetted his appetite, and a number of German critics had already praised or disdained the American feel of his work. Many of Palermo’s German contemporaries felt threatened by the invading American art, but he was passionate about it and introduced a number of Düsseldorf friends, including Richter, to the New York School classics. His move abroad may have also been a flight from an impasse. His productivity had slowed, and he was stuck. Trying to move beyond the cloth pictures, Palermo had ventured into the touchy realm of the monochrome, which so many artists hate to love. He painted three metal squares with three different odd-colored rust-preventive undercoatings, one of which he had recently used for a wall painting at Documenta 5. But the monochrome was no way out.Palermo explained that if he “were to work with canvas and stretcher, the whole image of the pictures would be a completely different one.” The phrase “image of the pictures” expresses a puzzling concern with the public perception of the material rather than the actual look of acrylic on metal—or not so puzzling, perhaps, if we imagine how strongly metal suggested Minimalism, especially when deployed serially in space, like so many Donald Judd boxes or Carl Andre tiles. As in the cloth pictures, Palermo also served up a hefty portion of American Color Field work—the painting presented as an object, in this case through its distance from the wall; the even, intense, and radiant color. American art for Palermo was a candy store from which to pick and choose. He eagerly browsed US art journals, but, not native to the American art scene and language, he remained partly free from the constraining discussion around opticality and the complexities of objecthood. In this way Palermo was able to make painting new.

While Palermo’s early two-part objects are still bound up with the romantic notion of a fragment yearning for wholeness, the elements of later examples from this body of work are increasingly independent and unrelated. And if he painted some of his objects with prominent gestural strokes in an expressionist manner, his brushwork betrayed itself more and more. The self-expression appears learned and false, stiff and mechanical. Likewise, Palermo’s signature triangle opposes tired notions of the spiritual in abstract art. In the well-known writings of Kandinsky on this subject, the tapering shape of the triangle is associated with dematerialization, while blue, Palermo’s color of choice for this shape, embodies the spiritual. But the imperfections of Palermo’s triangles—their slightly distorted angles and irregular edges—make them hopelessly material and real. And placed on large expanses of white wall or over doors, these tiny little things also have a comic dimension. Indulging in playful insignificance, they lightheartedly dismiss the gravity of abstraction’s spiritual legacy. The surface of the mirrored triangle can become dematerialized, for sure, but the surprise of finding a body reflected there throws one back to the here and now. Even in New York, Palermo kept making objects to confront his native traditions of romanticism and spiritualism, as if to measure the distance he had come from painting the German way.

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

—

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

—

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

—

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

—

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

—

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–